Making history: Celebrating a decade of igaming in New Jersey

To mark 10 years of regulated igaming in New Jersey, EGR talks to industry experts and those at the coalface back then about how the Garden State overcame initial geolocation and payment difficulties and what’s holding back more states from going down the same path

When then-New Jersey Governor Chris Christie gave his stamp of approval for regulated igaming on 26 February 2013, few would have expected the market to go live just nine months later – and with a synchronised launch so as not to allow any brand to steal a march on the competition. After a soft launch on 21 November, the Garden State became the third US state to offer online casino and poker, making its full debut on 26 November, coming hard on the heels of Nevada going live with just online poker from April 2013 and Delaware, which flicked the switch on casino and poker from 8 November that year.

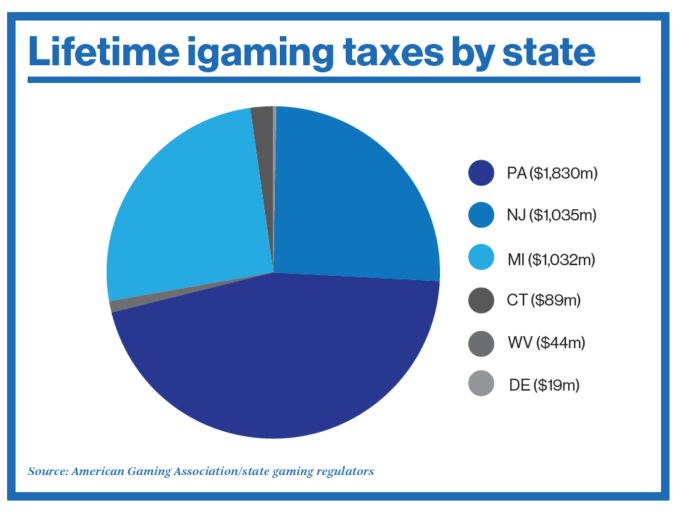

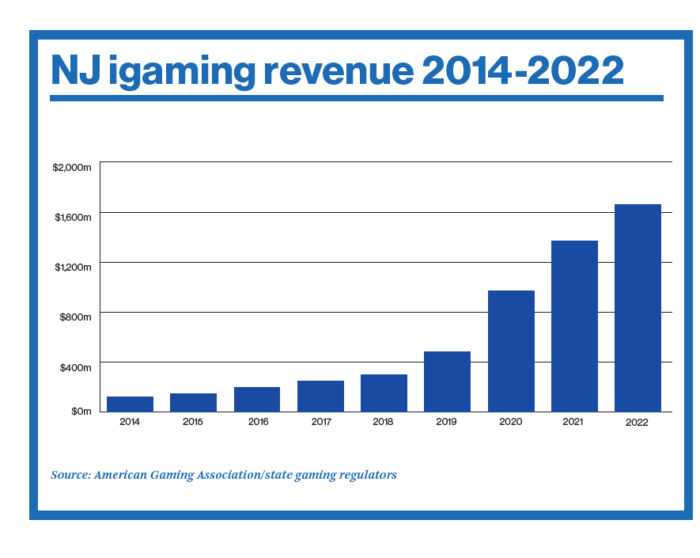

In November 2023, LinkedIn was awash with posts celebrating a decade since the launch in New Jersey. The American Gaming Association (AGA) shared standout data on the six states offering legalised online casino (New Jersey, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Delaware, West Virginia and Connecticut) having grossed $16.3bn in revenue and generated more than $4bn in state taxes since November 2013, despite only being available to less than 13% of US adults in their home state. The AGA’s figures show New Jersey is top of the leaderboard compared to its US igaming peers in terms of GGR ($6.91bn) and second for taxes ($1.04bn) between 2013 and 2023.

To mark the 10-year anniversary, geolocation supplier GeoComply ran a video series on LinkedIn outlining how those on the ground across key stakeholders coped with the pressure at the time. “Literally, our team worked 24 hours around the clock to get everybody across the finish line,” says Eric Weiss, who had been employed as technical services bureau chief at the Division of Gaming Enforcement (DGE), the state’s regulator.

In November 2013, Leverage Gaming Solutions founder Jesse Chemtob was employed by Betfair US as part of the “first boots on the ground team”. He jovially recalls working from a windowless office in Jersey City during what he termed “uncertain times” as to whether the operator would be ready to launch on time and how the market would react.

“Pre-launch, there was just a lot of hoops to jump through in order to get it over the line,” he explains. “There were a lot of crazy testing scenarios and things we needed to do to make sure the DGE was comfortable and that we were comfortable we had a compelling product to put out into market.”

Similarly, Prime Sports CEO Lee Terfloth, who was hired as an online gaming and poker consultant for Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa back then, describes it as “a chaotic time”. Having gone into testing on 23 November 2013, he and a colleague were up until the early hours of the morning writing FAQs for customers on topics such as geolocation and social security numbers (required for KYC purposes) to make sure the operator was ready to go.

Terfloth shares an anecdote on the infancy of geolocation at the time: “There was a player who was trying to geolocate from the Borgata where I was working. He sent me a message saying, ‘I can’t get connected. It’s not working. It’s not geolocating me’. So, I went up to his suite on the 40th floor and we found that the height restriction was preventing him from geolocating.”

As a senior adviser for GeoComply now, John Pappas recalls hearing from the team about “a lot of sleepless nights” when it came to ensuring the technology was fit for purpose and that customers couldn’t spoof their respective location. “Everyone wanted to make sure there were no issues,” he comments. “So, the buffer zones around borders were probably very tight. And over time, with more data, understanding of consumer behaviours and how precise they needed to be, the geolocation got significantly better.” And that improvement is clear as geolocation now has a 98% success rate, according to GeoComply.

As European players entered the state through local partnerships, such as bwin.party with Borgata and 888 through Caesars and Bally’s casinos, there was a stark difference in the geolocation methods used. IP-addressing schemes were applied in Europe to geofence entire countries, while in the US the focus was on geofencing state borders, which is much harder to do because IP addresses bleed across state lines.

Ocean Casino Resort CIO John Forelli comments on how this added an extra complication to the mix for European operators: “So, not only were we trying to do something completely different in New Jersey than we had done before, but even for our partners we were trying to do something that was different to how they were operating in Europe. The newness and the way we were approaching it was both really thrilling from the perspective of being on the edge but in a lot of ways daunting. It wasn’t for the weak of heart.”

Forelli, who was VP of IT for Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa when New Jersey launched, remembers going from a world pre-2008 where it was difficult to get new technology approved to five years later going full steam ahead with online casino.

“It was unbelievable to work through, to see the juxtaposition of a world that was very conservative and very tied up in tradition to overnight a new world of online gaming and the structures that came with it, such as account-based wagering, KYC, payment processing and geolocation,” he remarks.

Pappas, executive director of non-profit membership organisation the Poker Players Alliance (PPA) at the time of the launch, recounts the naysayers and sceptics who had their doubts about the demand for igaming and being able to keep it within state borders, yet the poker community played an important part in helping lawmakers understand there was a constituency of people who wanted to play poker on the internet.

After all, this was just two-and-a-half years on from what was coined ‘Black Friday’ when the Department of Justice seized the domains of leading sites including PokerStars, Full Tilt Poker and Absolute Poker, effectively shutting down online poker in the US. “The PPA made a numbers of visits to lawmakers in New Jersey, sent tens of thousands of letters and made phone calls. We were very active over a multi-year period to get that done,” Pappas explains.

Retail worries

In the early days, there were real fears over whether online casino would cannibalise bricks-and-mortar gaming revenue and, in New Jersey’s case, lead to staff layoffs at its Atlantic City properties. However, when the states began reporting revenue figures, this was quickly debunked. Chemtob adds the numerous land-based companies that were also operating online were validating the fact the vast majority of those signing up to open online accounts were “new and not in their customer databases”.

Forelli agrees there was almost no cannibalisation of retail. “There was just pent-up demand from people who wanted to do online gaming securely. We were cannibalising the black market with online. We weren’t cannibalising the existing land-based market,” he points out.

Once New Jersey was live, the challenges didn’t stop there. Chemtob recalls the customer pain points primarily around account creation and payments. There was customer hesitation over why they needed to provide information such as social security numbers when that wasn’t required by illegal offerings. He remarks: “Think about it from an operator perspective, you spent all these marketing dollars to drive customers to the site or the app, and then you’re losing a lot of them because of the funnel.”

There were also a limited number of game suppliers licensed by the DGE at the time, so a dearth of games to choose from. Payments was the other sticking point as banks would often decline online gambling transactions due to the merchant category code. In a letter penned in January 2015 by David Rebuck, director of the DGE, reviewing the first 12 months of regulated igaming in the Garden State, he referenced a new credit card code had been created and was expected to take effect in spring 2015. The letter, dated 2 January 2015, also mentioned how recent statistics at that time indicated about 73% of Visa and 44% of Mastercard transactions had been approved.

Pappas tells EGR that the initial payment problems stunted the market in the early years as the banks viewed it as a high-risk proposition. There was also an obstacle facing bricks-and-mortar casinos of understanding how they could use their online platform as a marketing tool for their physical arms to drive new customers to their casinos who they weren’t reaching before because a younger demographic was playing online.

Not only was there a need to inform the banks that online gaming was now legal, but the same applied to consumer education. Pappas particularly emphasises the importance of this when it comes to the illegal offshore market. “Why the illegal market still persists is because consumers find it easier to sign up for an offshore website than they do for a licensed one. The education needed is around customers understanding that when they put their money on a licensed site, it is secure, along with their financial information,” he stresses. He applauds New Jersey’s regulator for taking swift action against offshore websites by issuing cease-and-desist letters as well as contacting affiliate marketers to stop them promoting illegal sites.

Six months on from the November 2013 launch, Forelli said the state started seeing some traction. He notes that other state regulators had a favourable impression of how New Jersey was being run, especially from an AML perspective with every transaction being recorded, and how quickly the operation had stabilised.

A $1bn dream

Initial projections on the size of the New Jersey market had been branded almost comical at the time as Governor Christie had estimated $1bn in revenue by July 2014. In reality, the state reaped $123m in revenue in its first full year of operation in 2014, according to DGE figures. Ex-FanDuel general manager and VP Chemtob recounts the reaction to the early projections being touted. “People were laughing about what was assumed of Christie’s original estimates. When you’re starting from zero, it just seems unfathomable to get to where the industry is now,” he reveals.

Thomas Winter, former Golden Nugget Online Gaming and DraftKings executive, said in the aforementioned GeoComply video: “Everyone was making fun of Chris Christie for [saying] that igaming could gross $1bn one day in New Jersey. I myself am always a bit conservative but still I was hoping for $700m-$800m and look today, it’s getting closer to $1.5bn.”

Winter continued: “I’m in the camp of those who think we will have many more years of double-digit growth in New Jersey. Ten years from now, we should be anywhere between $2.5bn-$3bn, which means that online casino will generate as much revenue as all Atlantic City casinos combined, which is still mind-blowing to me.”

Despite the initial doubts, the size of the igaming market exceeded most expectations, especially since the industry hadn’t anticipated that sports betting was only five years away from being regulated, which Chemtob says “helped supercharge the trajectory of online casino growth” through cross-sell of sportsbook customers. He also credits live dealer table games for attracting customers who were perhaps hesitant initially to play online or didn’t trust RNG games.

Today, there are more than 30 online casino brands operating in the Garden State compared to 10 at the end of November 2013. In terms of financials, in Q3 2023 New Jersey reported a new quarterly high for igaming revenue (casino and poker) of $469.6m, according to the AGA. Figures from the DGE for October 2023 showed igaming revenue in the state had reached $166.8m, a rise of 13.3% compared to October 2022 while year-to-date stood at $1.57bn, an increase of 15.1% year on year.

Holding back the fears

With six states currently offering legalised icasino, most industry experts had expected the number to be higher by now. Chemtob voices his surprise that more states haven’t realised the obvious – that tax revenue generated from online casino is likely to be in excess of that of sports betting in states that offer both.

Similarly, Pappas had hoped for more than 10 igaming states by now but he acknowledges the difficulty with icasino because of bricks-and-mortar properties as well as numerous stakeholders being involved such as state lotteries and tribes. “Everyone is recognising that online gaming is the future, there’s no denying it.

“The demographics of a land-based casino are changing every year and the biggest operators that have a reach across the country are seeing it much quicker. The MGMs, Caesars and PENNs of the industry recognise they need to get on the online gaming train or they’re going to get run over by it,” he warns.

Ocean Casino Resorts’ Forelli also expected more states to have adopted igaming but understands the cannibalisation fear remains, especially among the tribes in states such as California. “In those states where the tribes have invested a lot of money, there’s a lot of concern over the billions they’ve invested in their land-based operations. Other states which have a mixture of public, corporate and tribes, like Michigan, have done a really good job in blazing the trail. But it’s surprising to me that it hasn’t evolved faster.”

CIO Forelli hopes that, as Florida gains traction, it could also influence California. “I feel like something will eventually happen in California and, when that domino falls, it will drop the other dominoes across the country,” he predicts.

Looking ahead at which states could be next to go live with igaming, Chemtob namechecks Indiana, Illinois, Maryland and, the biggest prize of them all, New York, all of which already offer sports betting and are meaningful in terms of population. “I would expect the online casino market in any state that comes online, if there’s sports betting already available there, to thrive and grow more quickly as there will be meaningful existing customer bases with their identities already verified and shared wallets ready to go.” The former FanDuel executive remains bullish on future states but forecasts it will be slower than most expect.

For Pappas, which states will be next to go live with igaming is “the million-dollar question”. He believes Maryland and New York are potentials, as well as there being some rumblings around Louisiana. Terfloth agrees the industry expected igaming to have taken more of a hold at a quicker pace, but sports betting has stolen the spotlight as “the hot new item”. However, he believes that once some of the large entities realise how complicated sports betting is, they will “turn their lobbying dollars back to igaming and it will come full circle”.

Another factor possibly holding back igaming’s progress is the concern over problem gambling rates with online casino. Pappas explains: “I hear it all the time from lawmakers, how do we stop addiction? People are on their phones all the time, so how do we make sure they aren’t abusing this product? But the evidence suggests in New Jersey that there hasn’t been a major increase in problem gambling.” He goes on to say that by sharing that data and illustrating the array of responsible gambling tools already in place will be important for new states looking to adopt igaming in the future.

In agreement, Forelli feels New Jersey’s heritage with gaming and lead on RG had given confidence to other states such as Pennsylvania to forge ahead with igaming, the latter of which became the fourth state to launch in July 2019.

Whether concerns around problem gambling rates for online casino or the cannibalisation of retail are the reasons for the slow igaming rollout, there’s no doubt it’s a profitable endeavour. However, with 2024 being an election year in the US, it makes legislative change unlikely and, with more stakeholders involved with online casino at a state level than sports betting, there are still hurdles to overcome. Whether online casino can negotiate those obstacles in a timely fashion remains to be seen.